April 29, 2011

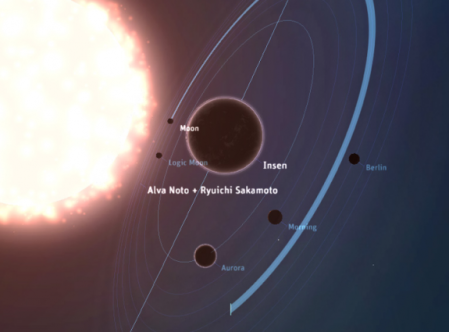

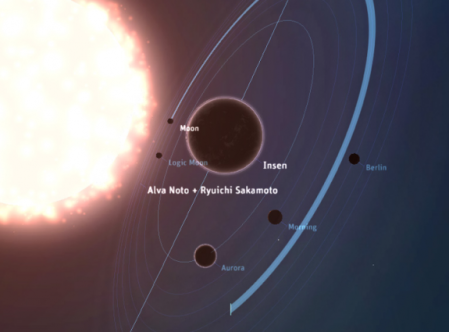

A new iPad app called Planetary, which drops on May 2, visualizes your entire music collection as a solar system: artists are stars, albums are planets, and tracks are moons. (a big thanks to FlowingData for the heads up here!) I wouldn’t be surprised if the idea came from Kepler’s idea of a music universalis, though this celestial take on music has never been expressed quite as literally before.

It’s sure to be a fun, immersive take on what has traditionally been a pretty unremarkable task: browsing your music. As with my recent posts about SoundPrism and iRig, the iPhone and iPad are starting to inspire musicians and developers to dream up completely new ways of visualizing and creating music. Traditional frameworks and systems (like the keyboard) are being questioned as new interfaces (like touchscreens) redefine what’s possible.

We’ll have to see if Planetary is actually a “better” way to explore music, but in the meantime I’ll definitely take “more stunning.”

Check out the official website: http://planetary.bloom.io/

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  art, Creativity, Design, Music, Nature, philosophy, Technology | Tagged: Bloom, iRig, Kepler, musica unversalis, Planetary, SoundPrism |

art, Creativity, Design, Music, Nature, philosophy, Technology | Tagged: Bloom, iRig, Kepler, musica unversalis, Planetary, SoundPrism |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

September 8, 2010

While neither philosophical nor particularly musical, the designer Mico has applied his graphic design prowess to music quotes. Enjoy. “Music Philosophy”

(You can also snag poster versions of your favorite quotes over at Etsy)

Related post: “Music philosophy,” combining music and graphics“

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  art, Blogpost, Creativity, Design, Great website, lyrics, Music, philosophy | Tagged: Etsy, lyrics posters, Mico, Music Philosophy, song lyric posters |

art, Blogpost, Creativity, Design, Great website, lyrics, Music, philosophy | Tagged: Etsy, lyrics posters, Mico, Music Philosophy, song lyric posters |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

August 4, 2010

The TED Conferences (self-described as “riveting talks by remarkable people, free to the world”) are a highly acclaimed series of presentations from the world’s most influential thinkers, innovators, and artists. Brilliant minds speaking about important topics in an approachable way.

I wanted to draw attention to one music-focused talk that I found particularly interesting. Watching the video would probably be one of the better uses of 20 minutes you ever spend in your life, but I wanted to point out some highlights and insights:

Benjamin Zander on music and passion

- Zander, in a compellingly funny and animated way, attempts to prove that A.) no one is tone deaf, and B.) that classical music is not dead. Both lofty ideas that are convincingly explained.

- “I’m not gonna go on until every single person in this room, downstairs, and in Aspen, and everybody else looking, will come to love and understand classical music.” You may be skeptical at this point, but aside from that: why does this statement matter? He goes on: “You’ll notice there’s not the slightest doubt in my mind that this is gonna work… it’s one of the characteristics of a leader that he not doubt for one moment the capacity of the people he’s leading to realize whatever he’s dreaming. Imagine if Martin Luther King said ‘I have a dream!…. of course I’m not sure they’ll be up to it…’ “

- He proceeds to play a Chopin prelude and, with some explanation (“This is a B, and this is a C. And the job of the C is to make the B sound sad.”) and one simple seed of an idea, transforms the listener into fully appreciating the piece on an emotional level. He includes comparisons to Shakespeare, Nelson Mandela, birds, Irish street kids, and an Auschwitz survivor along the way.

- “The conductor of an orchestra doesn’t make a sound… he depends for his power on his ability to make other people powerful. My job was to awaken possibility in other people.”

While music is one of the best ways to tap into emotions and creativity, I also argue that music is another form of philosophy. It’s one of the reasons I chose to study music at a university level, and why I continue to apply musical theory to almost every endeavor I take on. It’s a facet that Zander seems to appreciate as well. Studying and listening to music can unlock and refine a whole array of skills that are as useful in the music world as they are in other disciplines.

- The sheer art of listening (which is a learned skill, mind you, and requires lots of practice…) is probably the most essential ability one can possess when working with colleagues or holding a leadership position. Studying music teaches you to listen differently, more carefully, and to be perceptive of nuance and subtlety.

- Playing music with other people makes apparent the necessity for generosity, trust, cooperation, and teamwork. None of these things are ever mentioned when playing a 12-bar blues with some friends, but the best musicians (and leaders) practice all of them at all times.

- Music theory blends mathematical concepts with imagination, emotion, and creativity. This delicate balance of structural integrity and freedom is a struggle faced by most entrepreneurs and CEO’s the world over. Building an organization, whether it’s a church or school or community or business, requires a successful balance of Policy and Ideas. Procedure and Dreaming. This is something musicians practice daily.

Music-as-Philosophy is a topic best saved for a separate post, but the point is: music appreciation leads to the appreciation of other facets of life. Music is simply a means to an insightful end.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Business, Creativity, Great website, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Piano, Quote, Recommendations | Tagged: 2008, Benjamin Zander, Chopin prelude, classical music, Music, TED |

Business, Creativity, Great website, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Piano, Quote, Recommendations | Tagged: 2008, Benjamin Zander, Chopin prelude, classical music, Music, TED |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

July 9, 2010

Courtesy Jay Kennedy

“Looking at Plato’s works in their original scroll form, he noticed that every 12 lines there was a passage that discussed music.” – excerpt from NPR.org: “A Musical Message Discovered In Plato’s Works“

This article is fascinating to me, not because of the DaVinci Code-like revelation, but rather the emphasis on the number 12. It is a story that, yet again, links mathematics and music. It also dovetails nicely with a post of mine from January 2009 (“Twelve“), while referencing Pythagoras and the importance placed on ratio and proportion (also detailed here, “The Golden Page“)

There is no real conclusion drawn from the NPR feature, so we are left wondering why the preeminent thinker of 300 B.C. felt strongly enough about music to encode its defining principles into an otherwise non-musical work. The real takeaway here, and this is irrefutable: Plato felt compelled to draw connections between various arts and disciplines. Perhaps by conceptually linking disparate ideas, Plato believed he could reconcile the conflict and strife that always seem to arise when concepts appear at odds. (Science vs. religion, math vs. art, sculpture vs. painting, etc…)

These links and connections, as expressed through music, are what BlogSounds is all about.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Blogpost, Curiosities, Life, Mathematics, Music, Music Theory, Musings, philosophy, Quote, Science | Tagged: NPR, Plato, Plato Music, Platonic Music |

Blogpost, Curiosities, Life, Mathematics, Music, Music Theory, Musings, philosophy, Quote, Science | Tagged: NPR, Plato, Plato Music, Platonic Music |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

November 11, 2009

I was flipping through the book Everyday Tao and came across the entry for Music:

There was once a zither student whose master, frustrated by his pupil’s lack of musical progress for so many years, pronounced him unsuitable for learning. To understand how devastating this was to the young man, one must remember that playing the zither was considered a very high and demanding art, practiced only by refined and learned people. In addition, one’s master was like a parent. He or she was usually as dedicated to teaching as a parent is to rearing a child. So to be rejected by his teacher was a great shock to the student.

The master abandoned the young man on the shores of an island, leaving the student only a zither. Left to his own resources, the disappointed pupil provided first for his survival. The island, although uninhabited, had enough wild fruit and vegetables to sustain him. In the time that followed, he listened to the singing of birds, the chorus of the waves, the melodies of the wind. He spent long periods of time in meditation and musical practice. By the time he was rescued, several years later, he had become a virtuoso player and composer, far greater than his master: he had entered into Tao.

And so it is with us. We need teaching. But there is a point beyond which teaching cannot provide for us. Only direct experience can give us the final dimensions we need. That means learning from nature, and learning from ourselves. As long as we remember that, there can be no mistake.

So start playing.

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Books, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Practicing, Quote | Tagged: Everyday Tao, Music, Tao, zither |

Books, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Practicing, Quote | Tagged: Everyday Tao, Music, Tao, zither |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

August 29, 2009

There is little doubt that Apple is not just a company, it’s a zeitgeist. Apple products inspire brand loyalty that rivals Harley-Davidson’s (Exhibit A), with a reputation centered on quality and innovation.

But there’s something more insidious going on, and it has nothing to do with Apple Fanboys: Apple has taken our identities. Not literally of course, but it has taken our own identifier, “I.” For those interested in the philosophical implications of the self and what it means to be conscious and self-aware, “I” holds great importance. 18th century philosopher David Hume famously explored the concept of the self over time, and the book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid is a Pulitzer Prize-winning 800-page tome centered around defining the Self as a “strange loop,” and explores this concept through a wide range of analogies and examples. These are just two of hundreds of works based on “I”.

But what of “i”?

Apple’s iPod has relegated the proper noun “I” to the ranks of standard noun, and instead gives Pod the distinction. The Pod is the Thing, not us. The iMac, the iPhone… iWork, iLife… What happens when we start to use the lower-case “i” to refer to ourselves?:

i think, therefore i am not.

i don’t think this was an intentional move by Apple, but simply an unintended consequence. My feeling is that they used “i” because it looks like an upside-down exclamation point—a purely aesthetic choice. But perhaps they are playing with the use of i to represent imaginary numbers in mathematics, and used this to embed the concept of “imagination.” Or maybe “innovation” is the suggestion. But the connection between the imaginary and the self is a dark philosophical notion, one that we are all familiar with after having watched The Matrix.

At the end of the day the concept works brilliantly from a marketing perspective. To get someone to fall in line and do your bidding, you must first break the will. You must destroy your subject’s sense of importance and worth. “I am nothing.” Or, rather:

iThink, therefore iBuy.

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Life, Marketing, Musings, philosophy, Psychology, Quote, soul, Technology, Uncategorized | Tagged: Apple, Apple Fanboys, Apple Tattoo, David Hume, ipod, Mac, The Matrix |

Life, Marketing, Musings, philosophy, Psychology, Quote, soul, Technology, Uncategorized | Tagged: Apple, Apple Fanboys, Apple Tattoo, David Hume, ipod, Mac, The Matrix |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

July 19, 2009

“Creativity arises out of the tension between spontaneity and limitations, the latter (like the river banks) forcing the spontaneity into the various forms which are essential to the work of art or poem.” – Rollo May

Diego Stocco is a man who once saw a tree and decided to make music with it. Armed with some microphones, a modified stethoscope, a bow, and a Pro Tools LE system, he composed an entire piece of music using only unmodified sounds formed from the tree itself. Check out the final result here: Diego Stucco’s “Music From a Tree”

[Related post: “By Any Other Name…“]

3 Comments |

3 Comments |  Creativity, Music, philosophy, Quote, Rhythm, Science, Songwriting, Technology, Video | Tagged: Diego Stucco, Music from a Tree, Pro Tools, Rollo May |

Creativity, Music, philosophy, Quote, Rhythm, Science, Songwriting, Technology, Video | Tagged: Diego Stucco, Music from a Tree, Pro Tools, Rollo May |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

June 22, 2009

“In classical music, love is based on bitin’ — imitation. It’s not based on interpretation. A jazz musician, if he plays someone else’s song, has a responsibility to make a distinct and original statement.”

– Dr. Cornel West, philosopher, author, professor (b. June 2, 1953)

Leave a Comment » |

Leave a Comment » |  Jazz, Music, philosophy, Quote | Tagged: classical music, Dr. Cornel West, Music |

Jazz, Music, philosophy, Quote | Tagged: classical music, Dr. Cornel West, Music |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

May 9, 2009

This is a topic first introduced to me by one of my college professors in a Gustav Mahler seminar. He mentioned it only in passing, essentially a very raw footnote to some other point I’ve since forgotten. This forced me to connect the dots myself.

But first, a glossary:

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – (1749-1832) Arguably Germany’s greatest writer. Contemporary of Arthur Schopenhauer, a German philosopher whose concept of the “will” (i.e. man’s basic motivation and desire) formed the foundation of his ideas.

- Gustav Mahler – (1860-1911) Austrian composer and conductor. One of the most influential late-Romantic composers known for his rich and distinct use of the orchestra and all its colors. Many of the ideas of Goethe and Schopenhauer have made their way into Mahler’s work.

- Goethe’s Faust – His magnum opus. A tragic play in two parts, based on the German legend of a man who makes a pact with the Devil in exchange for knowledge. Also the inspiration for the second movement of Mahler’s 8th Symphony.

- Abbey Road – One of The Beatles’ finest albums, featuring the songs, “Come Together,” “Something,” “Oh! Darling,” and “Here Comes The Sun.”

The idea here is that Abbey Road has very strong connections to both Faust and Mahler’s 8th. Much like the supposed parallels between The Wizard of Oz and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, the connection between The Beatles and Germanic philosophical closet drama are likely equal parts serendipity, synchronicity, and unconscious inspiration.

The concept is best explained by making our way through Abbey Road’s sequential track listing:

- Come Together – Taken literally, the title of the first track mirrors the meeting of God and The Devil, propelling the album into the crux of the plot (The Devil bets God he can tempt Faust away from his ideals and pursuits). Through the lens of Mahler, it can also come to mirror the duality of his 8th Symphony–Part I being the setting of a hymn, and Part II being the setting of Faust. God and Goethe. Latin and German… both coming together to create one whole. I should also note that the first word of the first movement of Mahler’s 8th is “Veni,” the latin word for “Come.”

- Something – This is a love song, and pulls from Mahler’s hymn in its description of God’s love.

- Maxwell’s Silver Hammer – The cheekily bouncy tune describes Maxwell Edison, medical student, killing several people with a hammer, including the judge condemning him to prison. It juxtaposes nicely against the scholar Faust in his study late at night, pondering violent fantasies out of frustration.

- Oh! Darling – This song is a reassurance, an apology of sorts, that the singer will “never do you no harm.” I imagine Maxwell singing this song after awakening from his silver hammer daydreams, much like Faust is pulled away from his murderous reverie by the sound of an Easter celebration outside his window.

- Octopus’s Garden – An octopus’s garden, in which Ringo Starr sings that “we will be warm, below the storm, in our little hideaway beneath the waves,” is a sales pitch. Ringo is trying to convince the listener that “below” is where we should all spend our days. After Faust’s reverie is broken, he is approached by Mephistopheles in the same persuasive manner. This is when the Devil makes his offer.

- I Want You (She’s So Heavy) – This long, aching, humid tune is the epitome of raw desire. It mirrors perfectly Faust’s efforts to free Gretchen from prison and eventual death.

- Here Comes The Sun – This song opens up Side 2 of the Abbey Road LP. Part 2 of Faust opens with Faust awakening in a field of fairies, symbolizing a new beginning and a fresh start. The fact that both themes kick off the second part of their respective works is one of the more solid anchors of this theory.

- Because – This song echoes Mahler’s 8th more than Faust directly. The similarity is in the harmonies: Lennon, McCartney and Harrison all sing harmony parts that are tripled, thus sounding like 9 singers instead of 3. The second part of Mahler’s 8th is very much a “choral symphony.” In fact, Mahler once described it this way: “Try to imagine the whole universe beginning to ring and resound. These are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving.” Coincidentally (?), the song “Because” begins with the lyrics “Because the world is round…”

- You Never Give Me Your Money/Sun King/Mean Mr. Mustard/Polythene Pam/She Came in Through the Bathroom Window – These songs are short, interweaving pieces that form a “suite” of sorts and work together to build drama toward a theme of trancendence. This is the very same theme and technique employed by Mahler to set Faust in the second part of his 8th Symphony. The “here comes the sun king” lyric echoes the earlier song “Here Comes The Sun” and points to a higher power. In fact, the second part of Goethe’s Faust is said to be comprised of 5 acts—distinct episodes—”each representing a different theme.”

- Golden Slumbers – This song sits separately from the medley described above. It is not segued into, and introduces Faust to his “golden slumber”… that is, his final slumber, if you will…

- Carry That Weight – This song picks right up from “Golden Slumbers” and describes Faust’s striving and effort (this is Schopenhauer’s ‘will’). Goethe’s Faust is a troubled intellectual seeking “more than earthly meat and drink.” Mahler’s 8th describes the angels bringing Faust’s soul up to heaven. They even declare: “He who strives on and lives to strive/ Can earn redemption still.” The striving, this being Schopenhauer’s ‘will,’ is the “Weight” that Faust carried the whole time. It also features the vocals of all 4 of The Beatles, which is a fitting comparison to Mahler’s 8th, also referred to as the “Symphony of a Thousand” for its enormous use of singers and musicians. Themes from “You Never Give Me Your Money” are recalled, and the horns ring in a true transcendental sound.

- The End – “In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.” This is how The Beatles brought their work to a close, and it’s as fitting an end as Goethe could have ever hoped for.

- (Her Majesty) – This curious track was “hidden” on the original Beatles album. It’s not even listed on the first printing of the album cover. In this way, it stands apart from the underlying theme described here. But consider this: Mahler’s 8th symphony had strong themes that dealt with the Sacred Feminine, and was dedicated to his wife, Alma Maria. Also consider this portion of a note Mahler wrote to Alma in June 1906, describing his 8th Symphony:

That which draws us by its mystic force, what every created thing, perhaps even the very stones, feels with absolute certainty as the center of its being, what Goethe here—again employing an image—calls the eternal feminine—that is to say, the resting-place, the goal, in opposition to the striving and struggling towards the goal (the eternal masculine)—you are quite right in calling the force of love. Goethe … expresses it with a growing clearness and certainty right on to the Mater Gloriosa—the personification of the eternal feminine!

This last quote by Mahler himself describes the end of his own work, as well as the end of Abbey Road: “Carry That Weight,” “The End,” “Her Majesty”… all three referenced nicely in the context of Goethe’s symbolism.

Coincidence?

6 Comments |

6 Comments |  Album Review, Curiosities, Music, Musings, philosophy, Quote, Recommendations, writing | Tagged: Abbey Road, eternal feminine, Faust, Goethe, Goethe's Faust, Gustav Mahler, Mahler, Schopenhauer, The Beatles |

Album Review, Curiosities, Music, Musings, philosophy, Quote, Recommendations, writing | Tagged: Abbey Road, eternal feminine, Faust, Goethe, Goethe's Faust, Gustav Mahler, Mahler, Schopenhauer, The Beatles |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

April 26, 2009

Art Kane, "Jazz Portrait: Harlem, 1958"

The work of art is a copula: a bond, a band, a link by which the several are knit into one. Men and women who dedicate their lives to the realization of their gifts tend the office of that communion by which we are joined to one another, to our times, to our generation, and to the race.”

– Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  art, Books, Creativity, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Quote, writing | Tagged: Art Kane Jazz Portrait, Artists, Creativity, Harlem 1958, Jazz, Lewis Hyde, The Gift |

art, Books, Creativity, Life, Music, Musings, philosophy, Quote, writing | Tagged: Art Kane Jazz Portrait, Artists, Creativity, Harlem 1958, Jazz, Lewis Hyde, The Gift |  Permalink

Permalink

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark