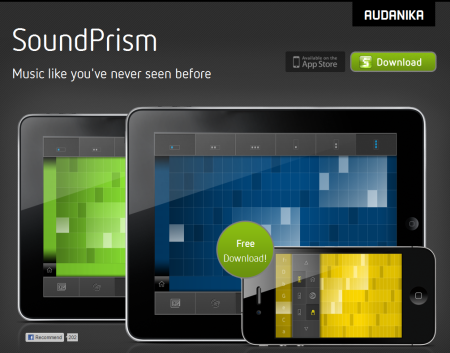

“Music like you’ve never seen before.”

SoundPrism is a brand new app that completely reimagines musical notation and how sound is visualized. The imagination required to do this is impressive, but it’s the nuanced execution and beautiful design that make it noteworthy.

At its core, SoundPrism is simply a music sequencer that is beautiful and easy to use. But that completely undersells what’s going on here and the level of consideration that went into its creation. To get a feel for what this app is all about, check out this introductory video:

Here are three key takeaways I want to point out:

“SoundPrism is based on the theory that music is interesting if you create tension and release it.”

This quote from the clip is absolutely true, and the foundation of all Western music theory. Music is a beautiful, elaborate departure from the “home” note (the tonic of whatever key you’re in) through various cadences and chord progressions that lead to the chord furthest away from home: the dominant, or V chord, thus creating a faint sense of unease (which I think we’ve all felt when we’re away from home…). The journey back to the tonic note leads to a sigh of relief as the tension is released. Everyone from Chuck Berry to Bach created music with this principle in mind, if only subconsciously. Ever hear of 3-chord rock? The three chords are the I, IV, and V of a key. The progression from I to V and back again is part of the propulsive force that makes the music so dynamic and exciting (along with the rhythm, of course). So while Beethoven’s journey through the 5th Symphony is undeniably epic and complex, blues is simply a distillation of the same tension-and-release principle, boiled down to the most essential chords while keeping the music interesting.

What makes SoundPrism so great is that its creators made a point not just to make the app easy to use, but to make the manipulation of tension and release easy to control. Why? Because it’s an essential part of making interesting pieces of music. It’s a fact that, to my knowledge, has never before been acknowledged by creators of musical software.

You don’t change keys, you change colors.

It’s a synaesthetic‘s dream. When you scroll up on the interface the hue shifts like the Northern Lights. There is no mention of being in F-sharp or B-flat, but rather in “green” or “purple.” I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the word “tone” is used by both visual artists and musicians to refer to roughly the same concept.

Major and minor modalities are treated independent of key.

Usually one will refer to the mode and the key at the same time. For example, “This song is in D major,” or, “We’ll be transposing this piece into G-minor.” But in SoundPrism you interact with modes in the same way you interact with notes, which is a massively different way of conceptualizing music-making. The odd-numbered horizontal lines are slightly brighter, and gestures along those lines will result in notes in the major mode. The even-numbered horizontal lines are slightly darker and correspond to the minor mode. The SoundPrism creators refer to these modes as “happy” and “sad” respectively, which isn’t a new comparison (this is how most musicians first learn the difference) but somehow seems more appropriate here.

This app, especially in its Pro version with upcoming Core MIDI support, shows a lot of promise for film scoring, demo production, and ambient soundscape creation. But what may be more exciting is what it could bring to the non-musician community, as it strips away some of the layers of technical skill and knowledge required to compose music in the first place.

The future definitely looks bright… and colorful.

Posted by Mark

Posted by Mark